In January of 1987, the two-story masonry structure located at 1515 Broadway Street in downtown Detroit was sold to Punch & Judy Productions. Coleman Young began his fourth term as mayor. The Detroit People Mover lurched into its counterclockwise errand. Earlier in the decade, Detroit reported a rapid decline in population and a first-time majority of Black residents. Next door at the Wurlitzer Building, a beaux arts tower clad in terra cotta, the last tenant had decamped. Its facade was adorned with slender columns, made to seem taller from the sidewalk by recessed spandrels, which brought to mind the company’s signature pipe organs installed both in houses of worship and houses of entertainment, and renowned the world over as the Mighty Wurlitzers. The structure at 1515 Broadway — flanked by a decaying tower, obscured by the tracks of a listless transit system, in the epicenter of an American city hollowed by a Reaganite vision of prosperity — commanded the sum of $37,940.42.

Years later, after a piece of terra cotta separated, crashing through the roof of its neighbor, the owner of 1515 Broadway displayed a sign offering a free coffee with the purchase of the Wurlitzer Building. It is a peculiar irony in the story of Detroit that a building that once upheld an empire of mighty musical instruments endangered one that had become central to the lives and livelihoods of a generation of musicians.

The terra cotta chunk narrowly missed the building’s owner and occupant, champion of music and theatre arts, Vietnam veteran, displayer of ironic signs, the impresario behind Punch & Judy Productions, Christoper Vincent Jaszczak. For more than three decades, until his death earlier this year, Chris Jaszczak’s venue at 1515 Broadway transformed the cultural landscape of Detroit.

Considered from the perspective of electronic music, January 1987 was extraordinarily lucky timing, equidistant from the milestones of the 1985 track, often cited as the first techno hit, “No UFO’s,” and the formation, in 1989, of DJ collective Underground Resistance. By the time I met Jaszczak, in the Spring of 2004, 1515 Broadway had long been established as an interface between techno music’s most ambitious, imaginative makers and its most curious consumers. I showed up at Jaszczak’s door, barely out of college and bursting with ideas about urban change. What would he think, I wanted to know, about a circulation plan of downtown Detroit organized around nodes of live music, such as 1515 Broadway? He invited me inside for coffee, willing to entertain ideas from an overzealous stranger.

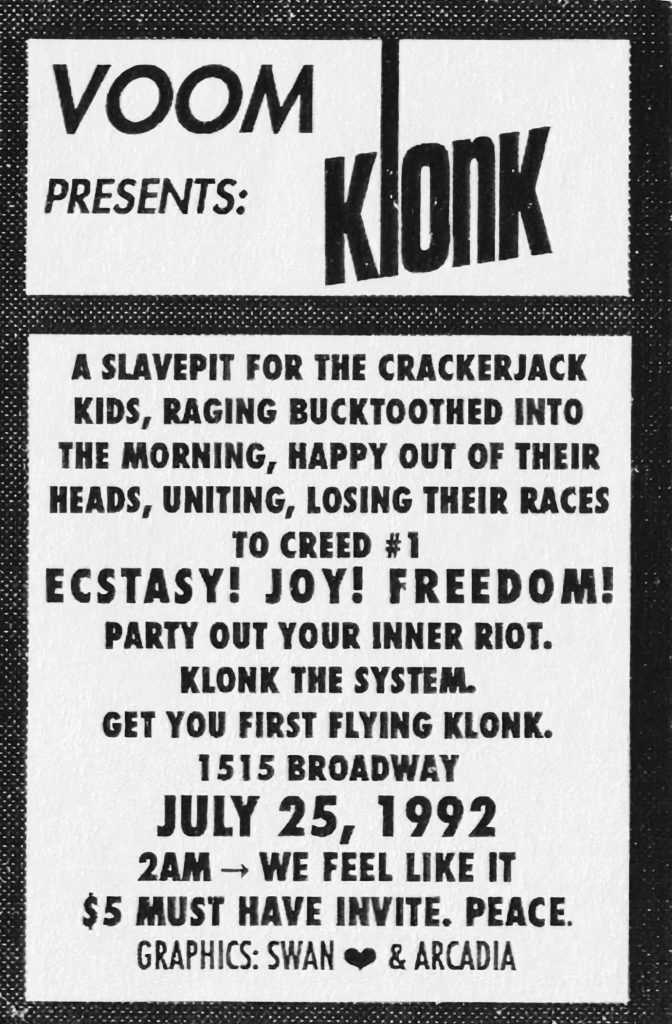

Opening doors to strangers was a hallmark of Jaszczak’s entrepreneurial philosophy. In 1992, Adriel Thornton, then an aspiring party promoter, approached Jaszczak with an idea for a monthly music series that foregrounded emerging electronic musicians. By day, Jaszczak’s building served as a performance space, a black box theatre styled after similar experimental stages in New York and elsewhere. But after hours, it was among the few legitimate venues that supported a new genre of music then emerging in Detroit. All through the end of the 1980s and the ‘90s, 1515 presented a roster of important Detroit artists in a modestly-sized, meticulously maintained, intermittently ventilated, legally licensed venue committed to the underground. Juan Atkins, Derrick May, Mike Huckaby, Mike Clark, Eddie Fowlkes, Marcellus Pittman, Derek Plasaliko, Alan Oldham, Erika, Claude Young, Theo Parrish, Alton Miller, Carlos Suouffront, and other electronic music makers appeared behind the decks there.

“A lot of people already used the venue to do underground parties, and he worked me into rotations,” Thornton said. “Definitely he opened the door and that’s how I got my start.” When Thornton speaks about the underground, he is not alluding to a questionable legal status: “it was a lot more weird then, more queer, more underground.” The Detroit underground, in his telling, was a loose aesthetic that had coalesced in the city, encompassing music as well as fashion, design, and the visual and performing arts.

“Techno in the early days was party music, but it was almost like jazz,” Thonton told me. “People who were making it were into other things: you’d see the same folks at the party and, like, at art film openings or gallery openings.” The polymorphously creative posture of 1515 was well-suited to an underground in which electronic music was just one stop along a cultural and social circuit Jaszczak recognized that the region’s most talented and daring people inhabited intersectional creative identities; in fact, Thornton himself acted in plays at 1515, in addition to staging parties. “Chris was an ally to different cultures who were marginalized,” he said. “Chris had reasons for supporting the underdog, for making space for people who were marginalized, or didn’t have a place.” 1515 offered that place: “it was like, the underground shit, the funky shit, the creative shit was created by all kinds of people.”

1515 Broadway cultivated an all-ages, all-kinds welcome attitude — an “antithesis,” as Thornton recalled, of the club scene. Careful in maintaining his above-board status, Jaszczak discouraged drinking, open drug use, and fighting. Whereas contemporaries like the Labyrinth exuded a dungeon aesthetic that amplified danger and kink, 1515 was firmly above-ground and surprisingly chaste. And unlike a subsequent generation of bigger clubs whose dress codes and VIP sections were determined to telegraph a feeling of glamour, 1515 remained unadorned and, for much of its history, teetotaling.

Jaszczak opened the doors to the freaks, geeks, misfits, and theatre nerds — after all, he was one himself. Born in Detroit in 1947, he was drawn to the arts after returning from two tours of Vietnam and earning degrees in political science and urban planning from Wayne State University. With his former wife, Jaszczak operated the Eastown Theater and, eventually, the Punch & Judy, a historic Grosse Pointe Farms stage.

People felt safe at 1515, dancing in the intimate space of a theatre. Outside the front doors, on the wide sidewalk of Broadway Street, young people leaned or squatted, talked and flirted, smoked cigarettes and found new friends. Patrick Russell, a DJ affiliated with the Interdimensional Transmissions label, remembers discovering like-minded people at 1515, a community of practice.The venue invited a “kind of a bohemian vibe: some Black, some queer, some Wayne State students,” he said. “It’s where I felt immediately at home.”

Some nights, the house was packed. Inside, more than a hundred people pressed against one other, sweating in the dim lights, vibrating with the bass of the speakers. Others, barely anyone showed up to the dance floor. That didn’t matter to Russell, for whom the experience of camaraderie didn’t depend on numbers. When, in 2007, Russell helped to launch the No Way Back party, he sought a return to that feeling, at once intimate and transcendent. The annual party, singled out by Resident Advisor among the great moments of the Movement festival, hit its stride when Russell and his colleagues relocated it to 1515 Broadway. “It was my favorite night of the festival weekend,” he said. “Not because I was playing the party, but because it connected the dots to the early days of the music. The scene out front was like reconnecting with family. Essentially, it became like a family reunion.”

At the No Way Back party, it was as if nothing had changed. But in fact, everything had. By the 2010s, raves, clubs, and festivals had remade an electronic music underground into a global entertainment economy. In 2007, Quicken Loans announced a deal to move its headquarters to Detroit, precipitating new infrastructure and private real estate development throughout downtown. The Wurlitzer Building, once a threat to the structural integrity of 1515 Broadway, had been sold to be repurposed into a high-end hotel, looming with a different danger.

When Jaszczak and I met over a cup of coffee in 2004, he listened attentively to my thoughts. We had been introduced by Derrick May, a foundational figure in techno music. May recommended an audience with Jaszczak to get a fair hearing — and frank critique. Might a cluster of open-air music venues, located at key intersections, function as an extension of Hart Plaza?, I asked. What would it take to equip vacant garages, pocket parks, and building podiums with a music stage? Would Jaszczak be able to produce a handful of simultaneous events, coinciding with the Movement festival? The idea was fine on paper, he told me. But it would implode under its own weight. I left 1515 with a sensation not of my ideas being crushed but that of being validated.

“Chris was very open-minded about creative ideas, especially from kids who needed a space to do something,” said artist and promoter Steven Reaume. Jaszczak launched many careers by validating others, by being available to sit and chat. “In his own way,” Reaume added, “he was always encouraging, but he was also very direct.”

In the 1980s, as an exodus out of Detroit was emptying downtown buildings, “there was a migration into the city. There was this whole culture of young kids who wanted to create something: DJs, poets, promoters.” They made their way to Broadway Street, whether through a network of introductions, an address photocopied onto a primitive afterparty flyer, or, perhaps, because of a gravitational pull that 1515 exerted. Thirty-five years later, now under the shadow of a boutique hotel, Reaume told me, “every time I would sit and talk to him, it was the same Chris.” Jaszczak held out as long as he could, hosting plays and parties, talking to people young and old, and making space for new cultural forms. He worked on his own terms, undeterred either by blight or by gentrification. And he remained an optimist for whom Detroit was a source of constantly renewing creative energy. “He was never against progress,” Reaume said, “he was just about the rawness and the beauty of the city he loved.”

Sid Gold’s Request Room, the new tenant at 1515, bills itself as a freewheeling, raucous singalong —“the Best Karaoke in Detroit, accompanied by a piano.” Revellers enter the bar from an alley and arrive into a darkened room, adjacent to a hotel lobby. Sid Gold’s is nothing like Jaszczak’s 1515 Broadway. Yet the past lingers; the mood is carnivalesque, the crowd queer. “Even though it’s in a fancy boutique hotel, they retain the quirkiness,” Reaume said, a little wishfully. “That’s something that Chris would have totally embraced.”

F. Philip Barash is a writer, urbanist, and educator whose work contributes to vibrant and inclusive public places. His writing about the intersection of culture and the American landscape appears regularly in national publications. A graduate of the University of Detroit Mercy, Barash came intellectually of age on the dance floors of techno music venues. He serves on faculty of Boston University and currently lives in Boston and Santa Fe, NM. www.philipbarash.com